A Middle Aged Man On A Mountain

Ruminations on climbing Slieve Binnian

A curious feature of the United Kingdom’s travel infrastructure is that it’s often cheaper and easier to fly from Newcastle to Belfast than to take a train from Newcastle to another major metropolitan hub in England. Not that I have a great deal of interest in visiting England’s cities these days. For the second year in succession, I decided to spend a few days in Northern Ireland, a place I’ve come to adore. I’ve made peace with the fact that in visiting the windswept coastlines of Northumberland, the quiet border regions of Scotland, or, more recently, Northern Ireland, I’m seeking a form of transcendence or attempting to unlock a gateway to ‘‘re-enchantment’’. If European Man’s earlier striving was for that which was unobtainable, perhaps now, in Winter, we yearn once more for a world unknown and unlearned.

The problem with over-intellectualizing what is equivalent to a ‘‘world feeling’’ is that in the act of doing so, the sacredness or specialness is brought forth and desacralized. Metaphysics becomes like an owl hoo-hooing at night, something audible but unseen, a presence understood in an intellectual sense but not truly there as a fact.

I stepped into the spectacular region of the Mourne Mountains, carrying my postmodern woes like an extra rucksack. I was adamant that I would dedicate one day to a solitary hike in mist-shrouded valleys and under the glare of granite-faced mountains reflecting a rare glimpse of the sun. It occurred to me that I was in a hyperreal land like Skyrim or the Lord of the Rings films. I remembered a favourite scene in Deer Hunter in which Robert De Niro stalks a stag across mountains as an orthodox choir soundtrack added to the sheer majesty of the cinematography.

Why the hell was I thinking of films and an old video game in this place? Once more, authenticity wriggled through my fingers like a little eel as I became conscious of the million media images embedded in my mind that denoted ‘‘awesome natural landscape’’.

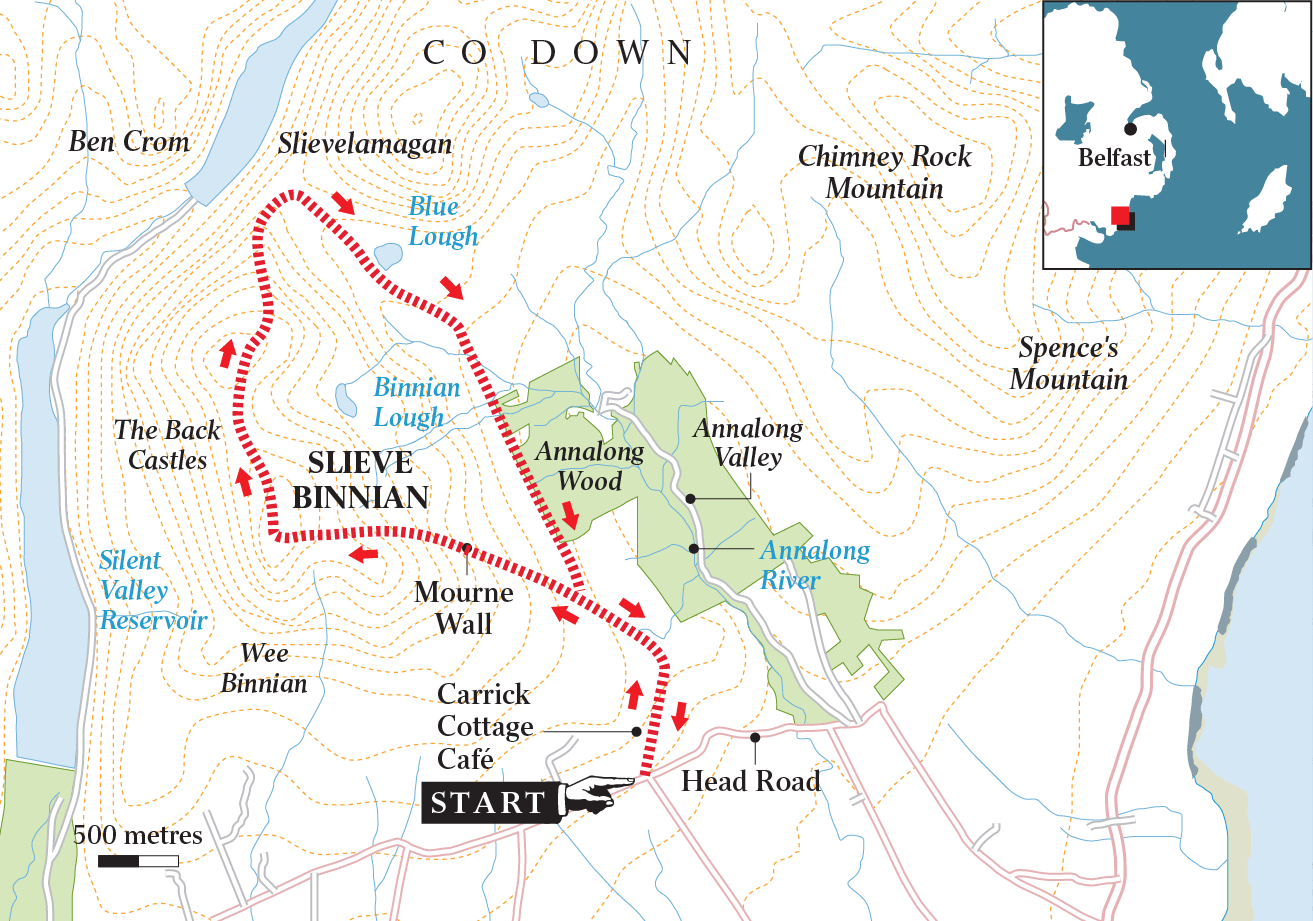

The trail I decided to walk was the Slieve Binnian circular, which was estimated to take about four hours. I’d been so preoccupied and distracted with the baggage of modernity weighing down my experience that I’d hardly even noticed the blurb online designating the trail as ‘‘strenuous’’ and ‘‘difficult’’. The first stage of the walk is a craggy winding trail through a valley between the Mourne Mountains themselves, which gradually impose themselves and increase in scale as the path winds deeper into the landscape. Truth be told, if I had been paying attention to the route map and not that I was viewing scenery through a filter of modern media, I’d have noticed that I was going anti-clockwise when it was strongly suggested to go clockwise and begin the main 700m ascent immediately along the iconic Mourne Wall.

The walk was gloriously free of other ramblers, and I counted just four people on the entire four-hour expedition.

After an hour or so of walking, gradually ascending, I passed Blue Lough and reached the sharp left turn at the foot of the mountain. Yet, I sensed that something special was awaiting me over the peak and went forward to be greeted by the magnificent view of Ben Crom and Silent Valley Reservoir.

The cost for the relative ease with which I had achieved this view was both swift and savage. The turn left ascending Slieve Binnian itself was an immediate mauling, encompassing a 700m rocky staircase that snaked its way up and up and up.

I’m no fitness fanatic; I do not jog or ‘‘work out,’’ and I’m also at the deeper end of my 40s. But neither am I a stranger to hiking, tough terrain, or the outdoors in general. Nevertheless, as my lungs heaved and scraped against my rib cage and I gasped my way inelegantly up the never-ending rocky stairs, I felt as if the mountain was punishing me for my initial indifference and somewhat pretentious attitude as I entered the landscape.

I was forced to confront my age, and whether or not I should continue. I sat gasping on a rock just 300m above the flat, pondering the people I’d known who’d died of heart attacks. What was I even doing up here? Some stupid notion of connecting with the eternal or inner poetry latent within us all? Yet, to turn back and scamper back to the safety of the flat trail would be intolerably emasculating. It had to be done.

I sweated buckets, and my breathing settled into a permanently rasping, cleave motion of seemingly never quite taking in enough oxygen. However, I also became more internally focused.

Unknown to me because I hadn’t bothered to pay attention to the route properly, Slieve Binnian doesn’t actually have one peak but two. As I wobbled onto the plateau, I was greeted by the first ‘‘Black Castle’’ which was essentially a giant outcrop of smooth granite boulders. Yet, this was merely ‘‘Little Binnian’’ and the highest point was set back into and above the direction of the main hike.

If this little escapade can be compared to Campbell’s Heroe’s Journey, I had reached the six O’Clock abyss of despair, crisis, and death/rebirth. I plumped my lathered, aching corpse-like frame down onto a boulder and took stock of the situation. The trail back was not heading along the ridge above the valley wherein I had crossed the threshold; it was meandering further away across the plateau and, shockingly, higher still.

I became aware that I hadn’t seen another person for about two hours. The sweat on my back grew cold, and I imagined how it would go down if some gym-bro in lycra discovered my corpse slumped by the boulders; which direction would the helicopter come from? Would they haul me in or just leave me dangling by the winch like a conker?

I moved on.

It began to dawn on me that I had been neglecting the stunning scenery in order to focus on the potentially ankle-breaking rocks and picking out the easiest lines to follow. The ridges I had gawped up at from the valley floor now lay hundreds of meters below; surprisingly, they even had their own loughs and ponds that formed the fonts for the nice waterfalls trickling down below. As I finally approached Slieve Binnian itself, I felt a profound sense of tranquility and peace. My breathing had stabilized, and I was no longer intruding on the most profound silence.

From the top, the lush green Ulster farmland stretched and tapered out towards the Irish Sea. But my attention was primarily drawn to the other grand peaks and mountains of the Mournes. Slieve Binnian was merely one, but I could count at least eight more: Slieve Donard, Slieve Meelbeg, Slieve Commedagh, Ben Crom, and Pigeon Rock Mountain. There was a synthesis and magical connection between them all as if they were slumbering Celtic Gods who all knew each other’s ways and probably disliked each other quite a bit.

Finally, after finishing the last of my water, I turned my gaze toward the coast and distant entrance, which seemed to be in another dimension. The plateau began to descend in gentle undulations, though by my reckoning, something was off because a descent that slow would need many more miles to reach the ground level than seemed feasible. The route planner told me to cleave to the famous ‘‘Mourne Wall’’ (an impressive feat of hard graft over the years in and of itself), but the distances seemed too short. Or, to put it more accurately, the hike down was going to be incredibly steep and demanding, and I had come the wrong way around.

The hike down amounted to a relentless grind over large boulders and rocks that poked out through thick, dark mud and small peat-filled puddles. Every single footstep threatened to snap my ankle or result in a slip. Bun shuffles and wincing in hesitation of disaster became an entire mode of Being, and I cursed the trail, myself, and the mountain a thousand times. Desperately and forlornly, I scanned the mountainside for easier walking, only to be greeted with swamp, deep mud, and crevices deeper than my height. My inner monologue became a litany of complaints and allegations against poor path planning, boots that lacked sufficient cushioning, the idea of hiking itself, and my Mrs who was frittering away my dying phone battery, asking how it could possibly take longer to get down a mountain than to climb it. I could see the main trail on ground level. I just couldn’t get to it without enduring the pounding, slumping, morale-crushing battle against the boulders and bogs.

Like attaining authenticity itself all over again, it was the presence but unobtainable nature of the ground-level trail that tortured the soul. Unlike the ascent, I knew that nothing particularly special waited for me at the bottom, just normal life. More than once, I sat, gasping, exhausted, and dripping with sweat in a heap of frustration and self-pity. The final battle was upon me, and I was losing, not against the mountain or my postmodern sensibilities and image-saturation, but myself. I found myself reduced to a sort of autopilot where all of my faculties were deployed in service of getting down as quickly as possible, jettisoning even time spent in self-doubt and futile pretenses.

Unceremoniously, I limped, heaved, and hobbled my battered body onto the main trail by the entrance and simply sat silently in the heather. The battery on my phone died as I searched through the photos I’d taken. It didn’t matter which was the most spectacular or ‘‘epic’’ photo because, despite the aches and pains, I had figured out that what brings modern men to such places isn’t a mission to find aesthetic or esoteric truths but to engage in a confrontation with themselves.

Seeing as how you wrote this, we can assume you safely returned from your ordeal with Nature!

My mother's family farmed in the lower pastures of the Mourne, for 100s of years, if not 1000s. I was very fond of my cousins but the harshness of the wilderness and perpetual leaden-skies, made family holidays a chore. I was embarrassed to tell kids at school I'd spent summer breaks in such a bleak and wretched rural war zone. There would always one, who refused to stop boasting about the confected Shangri-La of Disneyworld.

But with the rest of my folks, I tramped up quite a few of the Slieves from before the age of ten, guided by my grandma and her cocker spaniel. I'm glad I spent some of my youth following the footsteps of my ancestors and didn't waste time in the subtropics, queuing to gawp at Mickey Mouse. I feel sorry for those who did!

One thing about photos in these situations (that disappoints me) is that they flatten everything. So as serene as the pictures you provided are I know they were even more impressive in person.

I suppose in previous times there would have been shepherds following their flock up such summits.