Britain's Bonfire of Authenticity

On the Lions, Lambs and Lost in present-day Britain

A curiosity of Britain in the 2020s is that everyone knows in the marrow of their bones that things are bad while being cognisant that the current state of things has no formal expression in artistic or satirical form. Britain is now synonymous with words such as “Orwellian” and “dystopian” which are themselves linked with concepts like grooming gang, immigration, refugees in hotels, hate speech, NHS waiting lists, and variations on people being arrested for social media posts. Britain is the land of vape shops, potholes, foreigners everywhere who have long since lost their novelty factor, Turkish barbers, shuttered shopping centres, diversity bollards at Christmas markets, and, acting like a demented cherry on the cake, well-produced PR adverts everywhere imploring us to normalise it all internally.

Of course, a multitude of factors have led us to the current moment, but taken as a whole, it leads to a particular zeitgeist of degradation and demoralisation. Yet, again, this feeling has no artistic or cultural expression, and no investigation or contemplation of it happens within the mainstream. We live in an age begging to be satirised, lampooned, and railed against by comedians and intellectuals, but the conformity inherent within every institution kneecaps any attempt to give voice to what John Bull everyman is thinking and feeling.

I recently tweeted a playful and hyperbolic post to sum up the situation.

Naturally, such sentiment crosses the boundaries on touchy subjects such as political correctness, anti-white bias, immigration, and the corresponding surveillance state, as well as the ludicrous logic of the judiciary. The sentiment expressed is, I believe, commonly held, but the barbs are too sharp for the Establishment to process. So, it remains out on the periphery, along with everything else attempting to express authenticity.

To be a child in the 1980s was to live out your younger years in a cultural conversation awash in diatribes and dramatic presentations on Thatcherism. Channel Four primarily consisted of Jewish comedian Ben Elton, who excoriated every policy and utterance of Margaret Thatcher every week. The British liberal intelligentsia absolutely despised Margaret Thatcher and her policies, and they never tired of letting you know. To begin with, in the early 80s, Thatcherism was aesthetically expressed by poverty, hardship, and the inability of the working-class to survive within a world steadily being terraformed by neoliberal shock therapy. Long before Lord of the Rings, the late-great Bernard Hill was Yosser Hughes, the Scouse hardcase struggling to feed his children and spending days wandering the wastelands saying “Gizza job!” in Boys from the Black Stuff. Hughes was emblematic of the despair and squalor brought about by Thatcher, and the dilapidated urban decay of the council estate reflected the soul of the country.

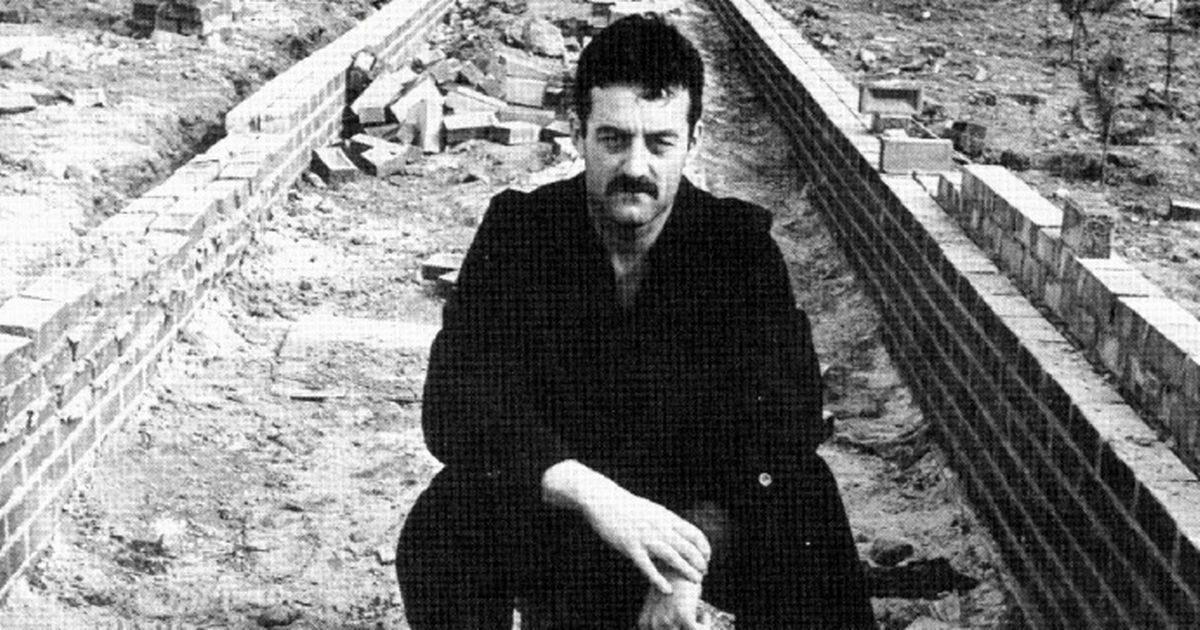

Closer to home for me was Auf Wiedersehen, Pet, in which Geordie bricklayers sought to escape poverty and unemployment by working in West Germany. The North East connection was apt because the Miner’s Strikes and the impoverishment of pit villages also added to the sense of decay and despair.

This gloomy grist was then fed back into the comedic mill of Spitting Image that could (not without reason) depict Thatcher and the Conservative Party as heartless vultures. Thatcher’s nigh-on religious devotion to free markets and a view of the populace as cut-throat go-getters who existed only within the context of a market would begin to bear fruit in the second half of the 80s. Thatcher was still a milk snatcher, but the working-class enjoyed the ability to buy their council houses, and upward mobility became more common.

Having previously delighted in firing cannon balls at Thatcherism on the basis that the working-class was being ground into the dirt, the liberal intelligentsia performed a pirouette in the second half of the decade and switched their criticism to the “greed is good” mantras and rampant individualism of Maggie’s worldview. The issue was no longer that Yosser Hughes could not find a way to feed his family, but that he was now a self-employed plumber with a white van who placed gaudy cladding on his house and went on holiday to Spain. Worst of all, the newly elevated working-class could very well turn into ardent Tory voters.

In his 1984 novel Money: A Suicide Note, Martin Amis’ main character laments:

I don’t want any more of this try, try again stuff. I just want out. I’ve had it. I am so tired. I am twenty-eight years old. I’ve been trying for twelve years. I’m exhausted. Looking forward to more of the same? I just want to get out. But there’s more. And not just one more, or two more, or five - where would you draw the line?

And:

Money doesn’t mind if we say it’s evil, it goes from strength to strength. It’s a fiction, an addiction, and a tacit conspiracy

Harry Enfield certainly does not easily fit within the broader politically-correct liberal mindset but it is nevertheless telling that his most famous character of the era was the boorish and braindead “Loadsamoney”, typifying the newly wealthy and socially inept working-class.

Thatcherism had smashed the Old Left, for better or worse, and the intelligentsia had to document what it meant for the nation. Indeed, one can’t help but speculate on the conversations at left-liberal dinner parties in Islington when the subject turned to their loss of a client group and what might be done to find a new cause.

The nation’s cultural and political mood found expression and intellectual contemplation that our current era lacks entirely.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Morgoth’s Review to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.