How Multiculturalism Consumes Everything

On the gravitational pull under which everything buckles.

The first time I ever saw the term “multiculturalism” was in a Sunday Times article around 2003, either written by Gordon Brown or featuring him, and I intuitively knew I was being lied to. I disliked the vagueness of the term, which felt entirely made up. Phonetically, it was ugly, with too many consonants cluttered too closely together. The sentence containing the term stated with insistence that multiculturalism was a fact, an objective lived reality, and that it had been for a long time. Multiculturalism was not something that was to come, but something that was already here. Britain was multicultural, and would not become so at some point in the future. This I knew to be false. Having spent almost my entire life in the North East of England, I knew that there were not many cultures or peoples; there was just us.

The general impression I had was that England was in the process of being terraformed by something similar to a science fiction World Engine. Moreover, I knew that we had never been asked, and that there wasn’t even much discussion about it. A question haunted my thoughts: if Britain was to become many cultures, then what would happen to us?

I was a grown man in my twenties, and that meant I had already accumulated decades of life experience before the term “multiculturalism” became formalised. I saw the Britpop band Pulp at Gateshead Stadium in 1995, and Britain was not as multicultural back then. I had spent years drinking in Newcastle and all across the North East, and nowhere was it multicultural. Bank Holiday Mondays in Whitley Bay were not multicultural, and the awful, backbreaking job I had in North Shields, surrounded by violent chavs, was not multicultural.

It was just us.

We didn’t have to discuss multiculturalism or immigration much because it didn’t matter to us. Places like London and Birmingham were known to have immigrant populations, but the perception was that they were static, an outlier not to be overly concerned about. The ethnic minorities were actual minorities, comprising 5% of the entire population, and even then, they were concentrated in a few areas.

In my adulthood, we have moved from a situation where immigration and multiculturalism were hardly discussed or even considered, to a situation where we discuss almost nothing else. The terraforming of England has cast into shadow every other facet of life; there is no escape from it, no outside of it. So all encompassing has it become, so normalised, that we hardly even remember what it was like not to be confronted by it every day.

There’s only so much mental energy, psychic dynamism, that a country has at its disposal, and in Britain, multiculturalism and mass immigration consume almost all of it. Right-wing conservative-minded people expend energy attacking it, liberals defending it. The power structure funnels colossal resources into managing, protecting, and expanding it.

In the name of multiculturalism, we have rewritten our history to place black and brown people in our past, choked ourselves on censorship, and strangled ourselves on regulation to ensure the wheels of the project keep turning. There is the core issue of raw numbers coming in, and the results of that in a physical sense in the real world. Then there’s the energy poured into the secondary effects and unending expanse of managerialist solutions to problems created by the initial act.

An issue such as Two-Tier policing exists because multiculturalism exists. Racial Equality Laws that form the foundation upon which Two-Tier policing occurs exist because multiculturalism exists. This disparity then sparks an intellectually charged debate regarding the problem, or whether the problem even exists. Statistics are required to prove the case one way or another, and then the reliability of the statistics is brought into question.

The perceived injustice of Two-Tier policing then gnaws away at the legitimacy of governance, thus creating further problems and discursive dynamics on the nature of government.

An organisation such as the BBC may hide from view the ethnicity of a murderer or rapist. Their logic in doing so is to keep greasing the wheels of the project, but in so doing, they merely open up another avenue of distrust and anger. To state boldly that an immigrant from, say, Africa, committed a terrible crime would play into the hands of “the far right”, so they play fast and loose with the facts to keep the metanarrative stable. This then creates a new dialogue.

Every single day, the country's political life is consumed by one issue or another related to multiculturalism. An entire conversation can take place around the chronic lack of housing, with one side arguing that there’s too much regulation and the other that there are too many people in the country. The same debates occur about NHS beds, traffic on the roads, available schools, the job market, or the lack thereof.

What may or may not be said or revealed. Who may or may not appear in a historical drama, or what the drama is about, and whom it offends.

The core of the regime, its spokesmen and water carriers, feign an ignorance in the face of these developments. In their framing, Britain is ticking over just fine except for a few outliers here and there. Nothing has changed, and if you point out a discrepancy, such as the ethnicity of Anne Boleyn, you’re inflating a minor issue of no importance.

The Death of Satire

The English comedian, Harry Enfield, made a return to the BBC between 2007 and 2012. Compared to his more observation-based comedy in the early ‘90s, there was clearly a more reactionary turn in his 2000s work. Targets included a multitude of establishment celebrities and pompous television presenters, Eastern European immigrants, the band U2, and, most brutally of all, upper-middle-class liberals.

Enfield was doing what all court jesters should do: delivering uncomfortable truths to those in power. The jester’s often painful or embarrassing jibes can be taken in good faith and acted upon, ignored, or worse. The idea is to convey what everyone outside the court is thinking and how the ordinary person perceives those with power and influence. While Enfield’s work of this era certainly merits a more focused analysis, here I’d like to zoom in on one sketch based on a favourite Enfield target, the show Dragons’ Den.

Enfield excoriates the ludicrously pompous panel of wealthy, high-status business owners and their seeming right to supreme arrogance justified simply by their wealth. In one skit, Enfield and Paul Whitehouse arrive to pitch an idea as bumbling English entrepreneurs trying to get the “Dragons” to invest in their concept called “I can’t believe it’s not custard”. The Dragons, also played by Enfield and Whitehouse, sneer and spit venom at the Englishmen and their stupid idea, swiftly sending them away with no investment whatsoever.

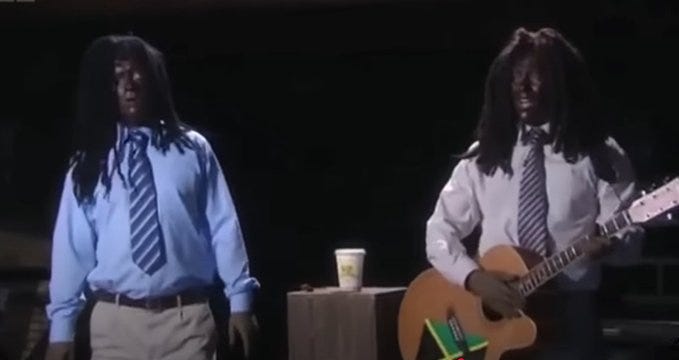

The two white men later return, adorned in black-face and Jamaican accents with a pitch called “Me kyan believe it nat custard” and the Dragons fall at their feet, showering them with money. They then begin to compete with each other in sycophantically grovelling, fearful that the least enthusiastic of them will be deemed racist.

The sketch hits like a thunderbolt because Enfield holds up a mirror to a particular class of people, saying, “This is what you are!” We, as the common folk, take great delight in this lampooning because we know it to be a painful, somewhat grotesque truth. In an ocean of noise, it is a clear, bright signal that something is not right.

It is both a commentary on multiculturalism and a critique of those with power and influence. Yet, for some reason, this sketch lands harder than, say, a Spitting Image sketch in the 1980s targeting Margaret Thatcher’s economic policies. There is a sense that an agreed-upon lie is being teased out into the glare of daylight and unceremoniously prodded and kicked about. The morality of the pretentious Dragons is a sham, and as such, their status is deflated before us.

Enfield revealed, in that single clip, the inherent fragility of the managerial classes dedicated to propagating via “virtue signalling” the values of the multicultural state. The millionaires of the Dragons’ Den panel adopt the attitudes and worldview of brutal free-market meritocrats, with the only subject of interest to them being whether or not a product or service is worthy of investment. Enfield implied that this worldview was a lie, a charade, and that they were no more outside of the central multicultural metanarrative than a Guardian journalist. The Dragons’ Den panel, and therefore neoliberalism, was not an alternative or competitor, but rather subordinate to the politically correct dogma of the age.

From the perspective of Britain’s liberal elite, Enfield committed a multitude of sins against them and their values, which probably explains why, after his show was shuffled off to BBC 2 to die, they never allowed themselves to be confronted with such lampooning ever again. The external frame from which people can gaze back into the general narrative would be kept permanently locked out.

Yet, this also marked a transition from a Blairite neoliberalism, in which the justification for mass immigration was to infuse British society with fresh energy and dynamism, into a more stagnant form wherein the upholding of the multicultural order became its own justification.

Strength In Division

Almost twenty years after Harry Enfield’s show aired, the narrative has been hermetically sealed for a generation and can only reference itself when attempting to make sense of British society.

Our diversity is our strength, but we must be ever vigilant against those who would seek to divide us.

After a recent terrorist attack in Manchester, in which an Islamic radical attacked a synagogue, Home Secretary Shabana Mahmood warned the country against becoming too divided over the issue. Yet, just a few days before the terror attack, Shabana Mahmood was herself at the heart of the discussion because she insisted that she was English. Many people disagreed.

Indeed, the entirety of the previous week had seen the Labour Party make stern speeches about the “Far Right” and Nigel Farage’s party Reform. The week before that, everyone was arguing about whether migrants were eating swans, and the week before that, the media machine whirred away in disbelief that Farage was changing the rules around migration settlement and proposing deporting up to 600,000 people. The week before that, a giant Tommy Robinson rally flooded into London to protest for free speech and an end to mass immigration.

Before the Robinson rally, a campaign of English flags was hoisted across the land, serving as a form of ethnic territorial marking. There was the story of the Scottish girl wielding an ax, and before that, the long, drawn-out saga of protest and betrayal of the Epping migrant hotel.

These stories were national news stories that leaped clear and free of the Xitter timeline.

The State and the establishment media like to paint a picture where unrest, acts of barbarism, or disputes are minor outliers to what is overwhelmingly a positive experience.

Obviously, this isn’t the case.

We do not merely “rub along” while an aloof state attends to economics and foreign policy; the primary activity of the state and media is desperately attempting to hold together the society it has created. Multiculturalism has become the axis around which everything revolves and shifts.

We can imagine Dutch society in the Middle Ages, driven by the impulse to reduce flooding by the sea, to wall off the flow, obsessively drain marshlands, and dig out dykes. Water, the sea, would have occupied the thoughts of every burgher and peasant, farmer and painter. Society would have been warped and buckled by the threat, and driven by a Faustian will to overcome it incrementally.

Japan’s unfortunate location atop tectonic fault-lines that routinely result in earthquakes tearing apart its cities could also be comparable.

I am often reminded of a curious Japanese anime from 1995 called Cannon Fodder. The story takes place in a fictional city, entirely walled, that dedicates itself to firing cannons across its defensive lines into the wasteland beyond. The basis of the entire social order and all of its resource management is to keep the cannons firing at the same rate, forever. The need to keep the cannons firing undergirds its education system, career paths, and intellectual life. There is no outside of the frame of firing the cannons, merely arguments about how best to keep them firing. Similarly, there is no real indication that an enemy is being hit, or even if an enemy exists. It is a society built on an absurdity. Yet the absurdity has become so normalised and entrenched in the city’s life that nobody can remember anything else.

There will be more atrocities in Britain because of multiculturalism. There will be more people going to jail for speech. There will be more hollow statements about unity being found in division, while division is also a threat to society. And every time it happens, the regime will insist everything is fine, and we’re bound to have a few bumps in the road before we can cruise along in normality.

But normality never actually arrives. Or rather, the unrest, the existential angst of the natives, the censorship and rapes and knife crime, and the alienation are the normative state of things, not, as we are told, bumps in the road.

An alternative timeline was possible. There would have been too many old people relative to young working people; the precious GDP would have collapsed. There would have been abundant housing, which might have resulted in easing the strain on family formation. In all probability, a different economic model would have become necessary. There would still have been a gravitational pull on society, in all likelihood centred on an ageing population.

In the here and now, though, in our timeline, it is demanded of us that we keep those cannons firing.

At least in the Japanese story the cannons are firing away from the city.

As always, the Voice of my People.

They told us not to have kids, now they blame us.