One Song, Two Souls

Meditating on an old song and the difference between the Irish and English expressions of it

I was recently on a road trip and, as is my custom, decided to take refuge in easy-listening playlists of songs primarily from the 70s and 80s. Nestled between Al Stewart’s Year of The Cat and The Alan Parson’s Project, I heard a song called Matchstalk Men And Matchstalk Cats And Dogs for the first time in decades. Hearing a pleasant but forgotten song again is a small pleasure in life, that moment of “Oh, I remember this one!” and the cracking open of associated memories. Yet this version of Matchstalk Cats and Dogs felt a little different, slightly unfamiliar and off. It was too folksy, cheerful, and, frankly, too Irish. But perhaps I was mistaken; maybe it had always been this way. I immediately carried out the inevitable Google search and discovered that this version was, in fact, a cover by The Fureys.

The Fureys version featured banjos, accordions, and lightly plucked guitars, giving it the distinct feel and “vibe” of a Dublin pub or country music festival. Fundamentally, it was optimistic, positive, and imbued with a gentleness and light-hearted sensibility. Pleasant, and I’m certainly no enemy of Irish Folk music, but it wasn’t what I remembered.

I then decided to track down the original to see if I remembered the song being the issue. I discovered that it was a 1977 folk song by a duo called Brian and Michael.

The difference in tone and mood was instantly noticeable. Gone now was the Gaelic gaiety and aura of bustling pubs in high spirits; as a Northern Englishman, I was transported back to the Social Club, redbrick terraced houses, and dilapidated industrial wastelands. Out were the accordions and mandolins; in were the brass bands and the eerily haunting boy’s choir.

The disparity between the two iterations of the same song made me ponder England and Ireland's long and troubled, often dark and bloody history. While the two nations have arrived at this moment in history bearing many scars and traumas, their cultural expression differs significantly. Remarkably, we can decipher many of the paths trod by England and Ireland by taking a closer look at the meaning of the song Matchstalk Men And Matchstalk Cats And Dogs.

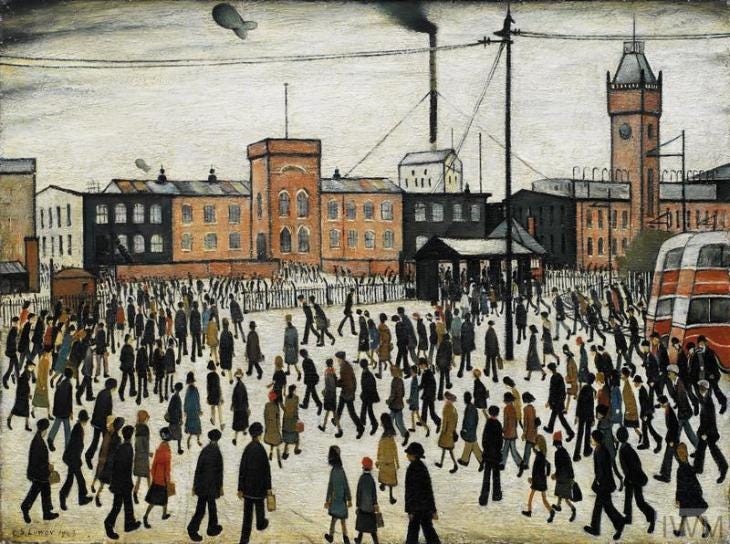

The song is based on the life of English painter LS Lowry. Born in the Manchester region in 1887, Lowry painted bleak depictions of the industrial powerhouse that was England in the early 20th Century. While he also painted seascapes and portraits, he became famous for his renditions of England’s stick-like masses toiling.

As the song tells us:

He painted Salford's smokey tops

On cardboard boxes from the shops

And parts of ancoats where I used to play

I'm sure he once walked down our street

‘Cause he painted kids who had nowt on their feet

The clothes we wore had all seen better days

In Lowry’s England, the people had been reduced to ants working toward the greater good of the British Empire. England and its cities were the coal-fired engine room and smog-addled centre of a machine spanning the globe. There are shades of Charles Dickens's Hard Times; Lowry is perhaps the antithesis to the earlier Romanticism that sought to re-enchant Europe after industrialization had stripped the land of its whimsy, looted its resources, and reduced its people to but quanta. Nowhere was this process more advanced than in England, which saw its people shuffled off the land into the packed tenements and terraces where they could be put to work servicing the Imperial Machine.

The song tells us that Lowry was not at first appreciated by the snooty art critics of the South:

Now they said his works of art were dull

No room, all ‘round, the walls are full

But Lowry didn’t care much anyway

They said he just paints cats and dogs

And matchstalk men in boots and clogs

And Lowry said, “That’s just the way they’ll stay”

Only to later change their minds:

Now canvas and brushes were wearing thin

When London started calling him

To come on down and wear the old flat cap

They said, “Tell us all about your ways

And all about them Salford days

Is it true you’re just an ordinary chap?”

The brass band (which I’ve explored in more depth here) became synonymous with the industrialized North primarily because factory owners and bosses wanted the men to engage in activities that did not lead to unionization and collective bargaining. Yet, the brass band also signals what the faceless masses’ endless work and graft would result in: Imperial Power and prestige. Thus, the brass band also has connotations of military expansion, national pride, and empire. Coal hewn from the rock in villages north of Newcastle would power the steel mills that cranked out armaments, guns, and the hulls of battleships. The sun would never set on the Empire, and the feet would rarely stop shuffling across the cobbles and workhouses of the smog-smothered heartland.

But the sun did set.

England, as a conduit of power and world affairs, was in a league all of its own, let alone in terms of comparisons to Ireland, which at the time of LS Lowry was still primarily rural. This is not to say that the Irish did not face their own hardships and historical trajectory; they most certainly did, but it is to illustrate the difference in national psychology and cultural symbolism. In the English version of Cats and Dogs, many signs and symbols point to profound nostalgia, brooding melancholia over a time long gone, a lament for a sun that set.

The song tells us:

Now Lowry’s hang upon the wall

Beside the greatest of them all

And even the Mona Lisa takes a bow

This tired old man with hair like snow

Told northern folk it’s time to go

The fever came and the good lord mopped his brow

The song tells us of a simple man of the North, self-taught, who, despite eschewing the grandiosity and pretensions of the art world, ended his days with his work hanging by the “greatest of them all”. It is almost a lament for England itself. The factories closed, the coal stopped flowing, and the shipyards became empty and desolate.

Therefore, the historical trajectories and experiences of the English and Irish are profoundly different. If the English toiled away sustaining the Empire, the Irish story is one of struggling even to have a state. Instead, Irish folk songs are imbued with homesickness, wandering and roaming within Ireland and far afield. In more technical terms, the English cultural psyche is locked into an organisational form toward a grand project, while the Irish soul reflects its absence.

As The Dubliners sang:

I’ve been a wild rover for many’s the year

and I’ve spent all me money on whiskey and beer

but now I’m returning with gold in great store

and I never will play the wild rover no more

And it’s no, nay, never

no, nay never no more

will I play the wild rover

no never no more

But this, my friends, is a story for another time…

Addendum

In 1995, the LS Lowry aesthetic, themes of Manchester’s post-industrial malaise, and the afterglow of greatness reappear again in Oasis’s song Masterplan.

Nice little piece and quite personal to me. My dad (born 1949), the son of barefoot mill workers, ran away from Northern Ireland when he was 13 with his mate to find work in England. His dad (my grandad), who died from asbestosis before I was born, literally working himself to death in the mills. After working in factories in Manchester, my dad returned home at 16/17 to get his parents to sign his papers for the British army. My aforementioned grandad was Irish fiddling champion and, as well as boxing at local fairgrounds, he at one time or another played fiddle with, and sometimes against (in competition) some very famous Irish folk players, including Paddy Riley and members of the Furies.

My family, who even in the 60s still lived in two-room houses provided by the mill owners, literally worked themselves to death in mills and factories, for a pittance. My grandmother widowed, poor, and with 8 children (yes, in a two-room house), was given money by the famous Paddy Riley when he saw the dire poverty she and her relatives were living in (this is now the 70s). He simply couldn't believe that Protestants in the North (a group he had always been taught were privileged) were living in such poverty.

All that to say, your piece really resonated with me mate. You said, "If the English toiled away sustaining the Empire, the Irish story is one of struggling even to have a state." I would just highlight to your readers that the Irish also toiled away for the Empire. During the time period stated, the 19th century, Irishmen sometimes made up, up to 40% of the British army, and the Irish economy (even during famine) provided much to the cause of empire, especially Belfast, which became an industrial hub right up to and including the Second World War.

Thanks again for the piece and for allowing me to share a bit of my own history, which ties in well with it.

Lovely piece of writing Morgoth. The images painted by Lowry could just as easily have been the scenes at Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast, when the workers poured out at the end of the day. Generations of men in my family worked there. At the shipyard’s peak 30,000 were employed there - my great-grandfather worked on Titanic as a very young welder. I grew up in a terraced house that still had the old outside toilet - this was the 80s. The industrial scarring on Belfast was atrophied by the Troubles - the modernisation that came for cities in England just didn’t happen in Belfast until much later.

My grandparents used to listen to The Fureys and Davey Arthur a fair bit and the Dubliners. ‘Fields of Athenry’ was another classic that all us kids knew by heart. A big favourite was the legendary ‘Catch Me If You Can’ by Brendan Shine. Lisdoonvarna, County Clare is mentioned in that song, a town famous for hosting an annual match-making event (also referred to in the song). I have relatives who live there. Sadly, it’s now famous for its large migrant centre, inflicted on the local residents by the globalist Irish government. Changed times. https://youtu.be/qkvUbgmzDB8?si=0yXAcdl0hLex0jDk