The Russia/Ukraine war will no doubt mark the beginning of the age of drone warfare in earnest. Reuters reports that Ukraine has orders placed for 300,000 drones of various types and 100,000 are being sent immediately into combat. Russia is set to produce 32,000 drones per year while also currently buying in bulk directly from Iran. The meme that goes around is that a slight young woman sitting in an office block somewhere uses a Nintendo joypad to kill brave men in mud hundreds of miles away, and there’s not much they can do about it. Drone warfare gives off the whiff of dishonour and underhandedness. Still, it is difficult to say exactly why. After all, is dropping bombs out of an airplane or launching ballistic missiles or machine-gunning men desperately climbing out of a trench any more honourable?

Eighty years after Dresden and Nagasaki, can we still even be shocked or depressed by the realities of industrial, mechanised warfare in which armies and entire populations are mere quanta to be erased from a spreadsheet using the “strikethrough” function?

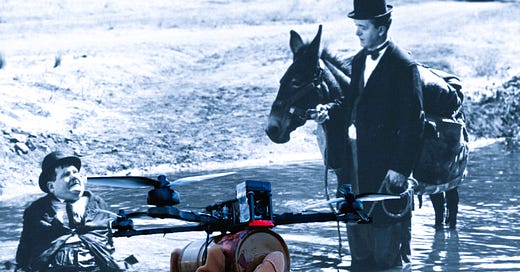

Nevertheless, seeing the realities of drone warfare via the grainy footage on social media left me at least with an uneasy feeling, but one that I could not pinpoint or explain sufficiently or adequately. Typically, such footage consists of soldiers of either side milling about in the oddly featureless Ukrainian landscape and then being hit from a distance or up close by drones or explosives fired from drones. In May 2023, footage was taken of a Russian soldier surrendering to a drone; we bore witness to the fear, dread, and utter helplessness of the man in the face of a remote-controlled gadget the size of a football.

More macabre incidents involve soldiers realizing that a drone is present and then desperately attempting to flee as the drone closes in. But where to flee to? There’s a brief few seconds of panic before the drone explodes. The camera turns to static, or if we’re witnessing from a distance, the soldier disappears in a puff of smoke as limbs and body parts are strewn across Ukraine’s fertile soil.

Yet, isn’t this just the reality of war? Of course, it is, but why does it feel different? Such gloomy thoughts recently returned to me in a setting as far removed from the warfields of Ukraine as one can be: a summery beer garden in Britain.

No British summer would be complete without the beer garden, and no beer garden is complete without the common wasp crawling into people’s drinks and sending people into a panic, comedically flapping and dancing around in an attempt to make the insect go away while not being stung. My father, who is entirely indifferent to the yellow and black striped peril, adores chuckling away at the discomfort and awkwardness of others trying to flee wasps. Not everyone is a dancer. Others try to stoically endure the wasp's presence until they, too, eventually crumble and begin waving their arms about like clownish cowards. This sad failure at trying to be brave is what makes my old man laugh the loudest. Flapping and dancing about because a wasp is close removes the mask of formality and “coolness” we wear in public settings. Our pride and ego vanish in a slapstick performance; the very absurdity of the situation removes any airs of pomp and seriousness. We are revealed as just human, awkward, fearful, and irrational but also deeply relatable and vulnerable.

However, let us crank up the stakes and tension a little. Let us assume that, in the event that a person was stung by a wasp, they had a very high chance of needing a limb amputated or emergency surgery. Is it still a joke? My father enjoys laughing at adults panicked by wasps, but he’d immediately kill it if it went near children. What if a wasp’s sting was lethal? Would the dancing and flailing of arms and shouting still be regarded with such mirth and ridicule? Only by a psychopath.

The juxtaposition of slapstick humour and awkwardness with death and gore flips the scenario into a realm of darkness and horror. A grown woman prancing around a beer garden in her heels and summer dress, squealing at the sight of an insect smaller than her fingernails, is inherently endearing and relatable. A man in military fatigues in a warzone is essentially doing the same dance, but he will die. Like the wasp, the drone is not inherently threatening to the rest of us, mainly because it looks like a toy or a hobbyist’s gadget. Witnessing a fully armed combat soldier shrieking back in terror and being chased by one is akin to watching an old Laurel and Hardy clip. Yet, death is the outcome rather than an acknowledgment of human fallibility and social awkwardness understood by all.

The contrast between revealing perennial traits of being human, in sameness, and the act of killing that human seems almost a betrayal or infringement of the nature of life, as actually lived rather than as an abstraction. The politicised human subject becomes mundane and normal again through the slapstick mannerisms and comedic routine.

However, perhaps I am viewing this through the wrong lens. Was this not always the way of war? Did soldiers at the Somme not write letters to their mothers complaining about the bread they ate or that their boots were uncomfortable? Did soldiers at Stalingrad not lament missing German beer or the family dog? The difference is we weren’t exposed to it.

There’s a reason Spielberg had a little girl wearing a bright red coat in the otherwise black-and-white Schindler’s List. World War II was a war of mass and quantity. Mass murder, mass bombing campaigns, mass conscription, and mass mechanized divisions were organised through masses of schematics and logistics operations. The individual was submerged into a statistic or a book full of statistics that would often be lost. Spielberg broke with standard film-making protocol to ensure we got the message: his people were flesh and blood individuals, not mere numbers.

Technology, whether social media or the drones themselves, has delivered a blend of the odd and macabre. We once more witness a brave man dying; we see the awkward panic and clownish body language of an adult fleeing a stinging insect, but we remain safe, and he is about to die. It is the sickest of jokes and there to be voyeuristically consumed as mere content.

At this juncture, I am forced to re-evaluate my own worldview, which tends towards a profoundly pessimistic opinion of “humanity”. The reactions of social media users to explicit imagery of human frailness and awkwardness immediately before death answer a question posed earlier:

Let us assume that, in the event that a person was stung by a wasp, they had a very high chance of needing a limb amputated or emergency surgery. Is it still a joke?

Unfortunately, my impression is the answer to this question is mainly yes.

Slapstick is a universal language; everyone can find humour in somebody sitting on a chair that collapses under them, resulting in them being inelegantly sprawled across the floor. The empathetic chuckle places oneself in the situation, feeling sympathy and relief. Others will laugh precisely because they do not have empathy, and it isn’t them on the ground in a vulnerable position, running from a drone or screaming about a wasp. The tragedy of Western liberals is that they assume they are in the position of garnishing empathy upon the world when they are the ones whose chairs collapsed, and they are the ones being stung by the wasps.

As the Bee Gees once sang:

I started a joke which started the whole world crying

But I didn't see that the joke was on me oh no

I started to cry which started the whole world laughing

Oh if I'd only seen that the joke was on me

Soon, if not already, Artificial Intelligence will pilot the war drones, and questions of human empathy and universal touchstones will be buried under the rubble of indifference once more. Perhaps when humans witness machines massacring humans almost of their own volition, there will be a late realisation of the sheer scale of the folly.

In the meantime, I have read that armies are going back to the good old-fashioned shotgun to shoot the damn things out of the sky like clay pigeons. And that would be a social media trend everyone can enjoy.

Artists and writers in the late 19th century feared the 20th century; they foresaw that it would herald the rise of the machine. Thomas Hardy saw the rise of the machine as the death knell for the pastoral life; machines negate the need for humans to toil the land. Tolkien saw firsthand the horror of mechanised warfare. In the 21st century we have the drone - the hunter is now the hunted. Soldiers in trenches, walkers disobeying Covid law in the middle of nowhere, no one is safe from the eye in the sky. I recently had the misfortune to see the film ‘Civil War’. The thing that didn’t make sense the most about that depiction of a war (and there was no shortage of choice) was the total absence of the use of drones….as you say, this machine is how war is waged now.

The only true thing about the meme appears to be that drone operators cam be slight and unable to fight their way out of a wet paper bag in real live. Drones, at least those used to kill individual soldiers, have to be controlled from close to the front, not some office block in the strategic depths. There is a recent video in which one such command center was overrun by advancing Russians. Like snipers, or guys carrying flamethrowers, drone operators have not much to look forward to when caught.

As to it feeling more odd than mass deaths through more traditional weapons, I agree that it is the individual aspect, one man killing another without risk to himself. We see similar in the Gaza conflict. The Hamas fighters killed individual people, the Israeli pilot turning an entire Palestinian family, grandmother to infant, into red jelly on a wall bombs an anonymous building.

On a side note, what the Russo-Ukrainian conflict revealed is that there is a shocking number of psychopaths on the Internet.