What If Elon Musk Actually Goes To Mars?

A speculative exploration on Mars being colonised.

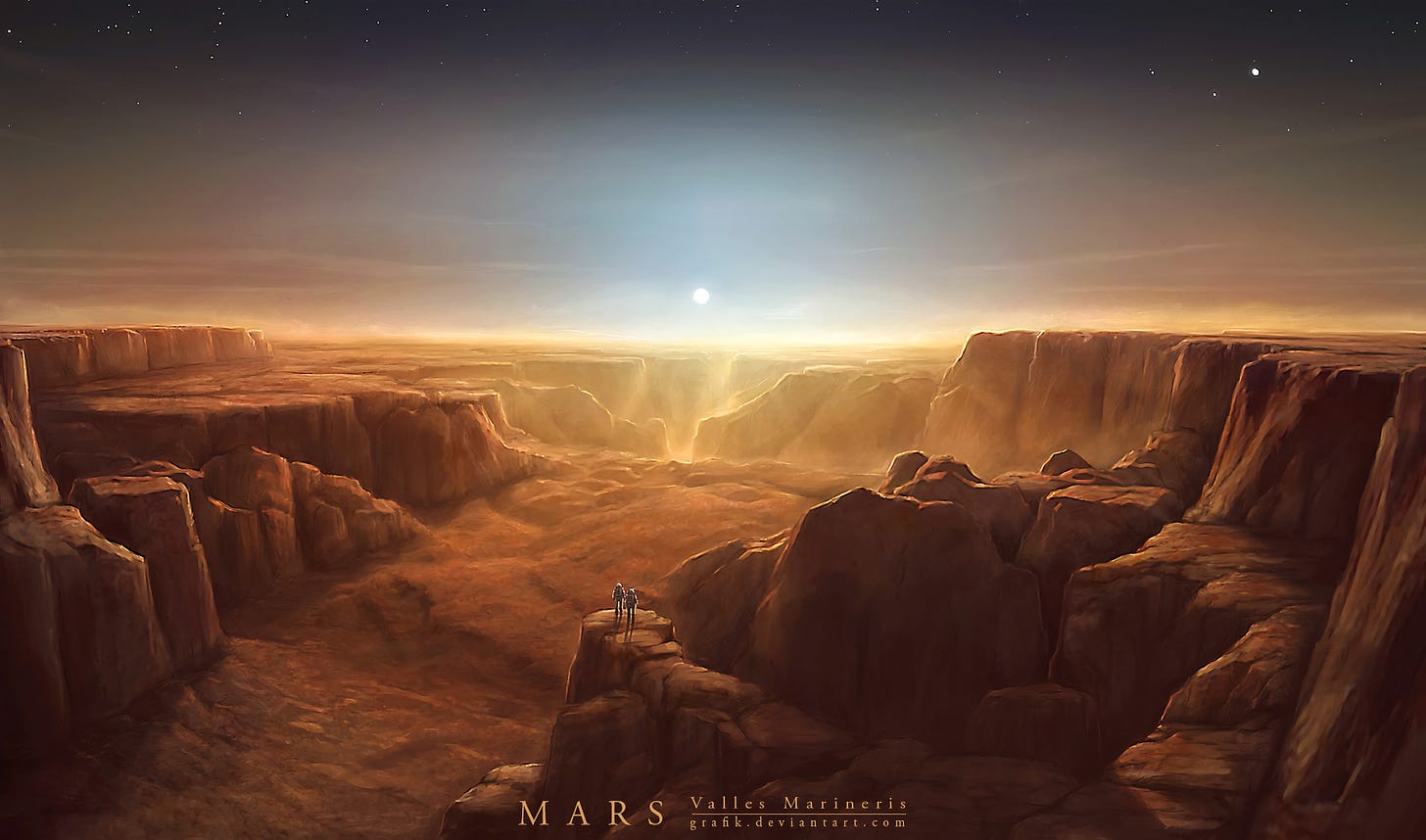

A 78-year-old Elon Musk sits in a chair hastily erected by an assistant in the perfect position to absorb the majesty of Olympus Mons, the highest mountain in the solar system. Olympus Mons is a plateau fifty kilometers wide and three times as high as Mount Everest. Billions of years ago, it would have been an island jutting from a sea. Mars’ seas have long since vanished, but humans have arrived. Musk activates the neuro-link chip in his brain to send a message to the chief engineer “Shall we climb it?”…

A few years ago, I produced a video in which I argued that Elon Musk would never reach Mars because the West, as it stands now, lacks the drive and spirit to do so. I argued that scientism and technocracy could provide the tools but not the reasoning and sense of awe that made men want to leap into the great unknown. It isn’t that I do not want to colonise Mars; I do, but to achieve it, we would need to peel ourselves out of the feminised, politically correct, Bugman drudgery that saturates our civilisation at present. I doubt that Musk ever watched my video, but his actions suggest that he also understands that a civilisation of Last Men insects no longer dreams of the stars. Nothing better exemplifies this lack of spirit than Musk’s engagement on X, where a post “owning” Kamala Harris gets 800k likes. In contrast, a post announcing the timeline and schedule for colonising a planet 208 million km away struggles to scrape into triple figures.

Musk’s timeline for colonising Mars goes like this:

The first Starships to Mars will launch in 2 years when the next Earth-Mars transfer window opens.

These will be uncrewed to test the reliability of landing intact on Mars. If those landings go well, then the first crewed flights to Mars will be in 4 years.

Flight rate will grow exponentially from there, with the goal of building a self-sustaining city in about 20 years. Being multiplanetary will vastly increase the probable lifespan of consciousness, as we will no longer have all our eggs, literally and metabolically, on one planet.

The tragedy of European Man in our current era is that adventurism and the Faustian Spirit must be justified through rational utilitarianism. To state “because it’s there” will no longer suffice, so a trip to Mars has to be explained through Sagan, Dawkins, and Asimov’s frames, in talk of having “all our eggs in one basket”. Scott of the Antarctic journeyed across the frozen void, dying in the process, for the glory of Britannia, King and Country, and because the unknown had to be conquered. Elon Musk claims he wants to colonise Mars so that human biomass has more spores embedded within the cosmos, making it more difficult for the cold-dead universe to eradicate us. I don’t believe that. I think he wants to go to Mars for, as the Irish would say, the craic.

Still, it is entirely possible that Elon Musk has gawped in horror at what his peers are doing with AI, genetic modification, and the skulduggery in secretive bio-labs and considered with good reason that the gravest risk to life on Earth is man, not meteor.

What I have previously described as “Centrist Caesars” can equally be called the Paypal Mafia or, to lean into Burnham, a counterattack upon managerialism from the capitalist entrepreneurial classes. You don’t get to Mars by being forced to hire more Haitians; you get more managers. It stands to reason that the initial expedition to Mars will comprise elite human capital who think above and beyond the petty political fads of the age.

Let us now indulge in a whimsical exploration of how Musk’s Mars expedition could unfold based on the timeline provided and beyond.

Phase 1

Despite the best efforts of Elon Musk and his legions of fans, the spectacle of a manned spaceship departing for Mars lasted only 6 hours on the feeds of the social media-consuming masses. A few hit-pieces rolled out in establishment media, focusing on the monumental cost of what they regarded as an indulgent folly by a half-crazed billionaire. Much was made of the undeniable fact that, for the same price as the Mars expedition, fixing the decaying infrastructure, helping the masses of unemployed due to automation, and various social programs and trans acceptance education would be more beneficial. An 82-year-old President Donald Trump celebrates the launch as a prime exemplar of America being back, but he is widely attacked for it, as is Musk.

Nevertheless, the launch is a success.

Phase 2

The first wave of pioneers, eventually consisting of around one thousand people, swiftly found themselves disoriented by distance, the alien nature of Mars, and the lack of the promised internet connection. Their cultural references and touchstones failed to explain or process their surroundings fully. Many of the pioneers suffered from an overpowering feeling of existential gloom and anxiety. The first two years of the expedition are saturated in an atmosphere not of elation but of unending crisis and fear. This feeling of terror and dread would later be known as “Mars-Shock”.

Moreover, the sense of abandonment is compounded by the realisation that the dulled attention spans of those on Earth have already forgotten about them entirely and care not one jot about the ordeals they’re facing.

Phase 3

When Elon Musk arrived at the Mars colony called “Teslaville” in the mid-2030s, the disillusioned colonists greeted him with substantial hostility. The IVF treatments had been a success, and baby production was going swimmingly, but the sense of crisis and lack of direction had become acute. Ensconced within their concentric rings of carbon domes, the pioneers often felt like slaves but could not return home or “touch grass” meaningfully. Musk brought with him yet more bad news.

Due to the Earth’s chronic competency crisis and the West’s recently collapsed economy, the infrastructure and engineering components required to organise a return journey were disappearing. There would be no return journey, and no more pioneers would join them.

Within the pioneers, a sect emerged that held that Earth was a worn-out clown show, decadent, lazy, and stupid. The question posed was, “How can they, with so much, fail so miserably while we, with so little, strive and survive in what looks like a vision of hell?”

Gradually, an ideology of separateness and distinction began to circulate. Independence was whispered over quiet evenings before screens filled with Earth in chaos. The alien nature of Mars began to have an almost metaphysical effect upon the colonists; an acute mysophobia became manifest with colonists showering and washing multiple times a day, fearful of infection, ever watchful for specs of red dust appearing in their clothes, bedding, or workplace. Wearing white became a mark of high social status. It also became common to see young women with shaven heads to ensure they weren’t contaminated. Traits, habits, and rituals utterly alien to people on Earth became commonplace. The sense of “Otherness” arose naturally.

Phase 4

As an elderly Elon Musk closed his eyes for the last time before the majesty of Olympus Mons and Taylor Swift was declared President of the United States of America, the fabric of Dome 3, the second-largest city dome on Mars, blew out. What would become known as “The Great Rip” resulted from a rogue titanium strut gently rubbing against the sealants clasping the protective fabric to the construction frame. A quarter of all the colonists were sucked out into the deep red gloom. The outside surface of Dome 3 was littered with colonists wearing emergency masks begging to be allowed back inside. However, this would require cutting through and permanently compromising Mars’ second-largest structure. The Independence Sect, now the most vocal and best organised, decided to save the dome for the greater good and allow the colonists trapped outside to die.

The social fabric within Teslaville began to break down as family and friends stared in horror at the faces of loved ones slowly running out of air and dying in agony draped across the canopy of Dome 3. The corpses would lie strewn across the outer dome for weeks. The Independence Sect recruited the most physically intimidating men as muscle to keep the traumatised colonists in line and ensure that food and baby production continued apace. The hysteria and irrationality witnessed during the Great Rip convinced the Independence Sect to sweep away what they regarded as childish and infantile democratic ideals. Instead of every colonist being consulted and raising their hands at meetings, the newly formed Council Of Ten would make all decisions on their behalf lest they descend into weeping and emotionalism once again. The Council of Ten would themselves elect a Supreme Executive, who became known as “The Monarch of Mars”.

Dwelling at the top of the social hierarchy, the Council of Ten was above the cleansing rituals because they never entered any spaces with the remotest chance of red dust landing on them. This, however, was in stark contrast to the Monarch of Mars, who adorned himself in a blood-red cloak to signal that he was of Mars and not alien to it. Thus, upward mobility took the form of the lower ranks attempting to become more attuned to Mars and less alien while becoming ever more estranged from memories of Earth, vegetation in the wild, and open stretches of blue water.

The memory of the Great Rip would be sanctified each year with ritualistic fasting and a cleansing of all infrastructure. The Monarch of Mars would spray blood-red dust across the masses who would writhe and roll about until they were bruised and disoriented. The masses would wear red gags to performatively suffocate and silence themselves to memorialise those who died in the catastrophe.

Phase 5

In the 2130s, a century after Elon Musk had attempted to plant his liberal ideals on Mars for safekeeping, the Monarch of Mars, resplendent in his deep red ceremonial cape, arrived in Earth’s orbit aboard the solar sailer “Crimson Mons” spaceship. The litany of disasters, wars, collapses of every kind, and demographic decimation meted out to the finest human capital on the planet left the colonists speechless. However, it became apparent that the original pioneers and Musk’s team had sought to escape “humanity” more than Earth itself. A sense took hold that Mars would not simply be a replica of Old Earth, with its sclerotic bureaucracies, insane political doctrines, and economic gangsterism; instead, it would forge an entirely new civilisation with its own spirit and sense of wonder and purity.

In what would come to be known as "The Second Great Rip," the Martians turned away from Earth. Or rather, their identity as Martians, a distinct, clannish people with a different world picture, broke through the permafrost imposed upon them by the Old World. Their world would be a civilization of purity, minimalism, and a reverence for Spartan comforts and luxuries—as barren as Olympus Mons and deep as the oceans of red dust.

Elon Musk has often said that his philosophy was influenced by Isaac Asimov, notably Asimov’s Foundation. In Foundation, a mathematical genius calculates that the galaxy-spanning civilisation he lives in has already peaked and that the future will be one of wars, civil strife, and collapse. The genius, Hari Seldon, developed a program to seed civilisation on a distant planet called Foundation by planting it with all the scientific and historical knowledge available. A few years ago, I made a video that compared Asimov’s liberal humanist views to Spengler’s civilisational cycles. Fundamentally, the question comes down to the feasibility of “shorting” the cycle of decay and collapse by using the resources of one civilisation to create another, crucially bypassing the ages of irrationality, religion, and superstition. In Spenglerian terms, this would equate to maintaining a state of existence permanently within the summer phase, presumably resetting in autumn, thus bypassing both spring and winter.

An expedition to Mars would necessarily consist of Millennials and Zoomers, with Gen Xers such as Musk himself in leading roles. In other words, they’d be liberals from similar backgrounds with similar cultural outlooks and values. It seems to be taken as read that the Mars colony would replicate a form of 1990s liberalism, free-thinking go-getters carving out a new life away from the woke crazies and the suffocating bureaucracy of Earth, and the West in particular.

Mars would be their Trantor, and with internet access beaming across the void, they could easily keep pace with the latest Marvel movies, memes, and political story arcs.

Yet, as I noted in my whimsical story, the raw material conditions of life on Mars would undermine and transgress postmodern pieties and liberal assumptions.

Could a physically isolated community 140 million miles from Earth, numbering a few thousand at best, countenance abortions or women using the pill? Would colonists be allowed to vote themselves an extra portion of rations? What would happen if the technicians responsible for purifying the oxygen tanks went on strike? What measures could be taken to prevent the emergence of an independent faction organising itself? Would their “free speech” be curtailed? If so, on what grounds, given that the man behind the entire enterprise is perhaps the famous advocate of free speech today?

I do not intend to denigrate the noble cause of attempting to colonise the great beyond—far from it. However, one gets the impression that jettisoning the liberal pretensions with the propulsion engines would make people see the project as a failure because liberalism has become synonymous with “civilisation” rather than being seen as an offshoot growing from a bough in a mature tree. Here, we run into the folly of Asimov’s Foundation once more. If civilisation is to be planted on Mars to safeguard “consciousness”, it does not follow that the colonists will retain their late civilisation mores. On the other hand, if the project is to explicitly and openly secure the foundation of an entirely new civilisation, then there’s no reason to believe it should be any more liberal than the Holy Roman Empire, Hellenic Greece, or Pictish Scotland.

There is a bitter irony to all of this: in our decaying world, we seek ways to escape, whether into the digital void or the immensity of the solar system. We have developed the tools and technical brilliance to accomplish both, perhaps. Still, the grander tragedy is that we remain constrained by liberal assumptions of rights and declarations, constitutions, and egalitarian priors. We carry it with us like athlete’s foot. The colonists of Mars will set foot on the planet once associated with a mythical God of War, and they’ll compare it to Hollywood films while taking selfies in their protective suits. They will be in for a painful awakening and their values system will fail them.

An eventual colony on Mars will probably begin to resemble a Dark Ages village more than Star Trek within a few years, and that will probably be the most significant discovery and challenge that awaits the Space Man and his team.

Then again, it’s also the most significant challenge facing our people and civilisation.

To be fair to Musk's attempt at motivation, "because it's there" has only ever applied to exploratory expeditions, and even then only some of them: most expeditions were surveying the land looking for mineral resources, arable farmland, or navigable passages for trade. Actual colonization has almost always had an economic motivation - fishing settlements, plantations, trading outposts - with a few colonies (e.g. the Puritans in New England) having ideological motivations.

There is absolutely no economic motivation for Mars settlement. The closest one might find is mining, but asteroids are much easier. Thus, the only possible motivation is ideological. Musk goes with "protecting the species from extinction by asteroid bombardment", probably partly sincerely, and partly tactically: it sounds better than "Earth governments are insane and we need outposts beyond the global prison grid they're constructing". Which, incidentally, is almost certainly why our governments are so utterly disinterested in building a permanent, self-sustaining off-planet presence. Over time those colonies will become independent, and therefore potentially hostile, and since they have the high ground and can drop rocks on Earth (see: The Expanse) to build those settlements would be a very expensive way of screwing yourself in the long run.

As to liberalism: for a whole lot of reasons, many of which you mention, this is likely maladaptive in space. But, on the other hand, there's another kind of freedom. Space is impossible to control. It's too big. People can always just go somewhere else. It's the Infinite Steppe. The freedom it offers is more of the sort enjoyed by nomadic steppe tribes or high seas pirates than that of liberalism. And that might not be a bad thing.

"Moreover, the sense of abandonment is compounded by the realisation that the dulled attention spans of those on Earth have already forgotten about them entirely and care not one jot about the ordeals they’re facing."

The above quote is I think horrifyingly the nub of the problem and shows we're clearly a different culture from the Apollo era.

Our destiny among the stars seemed certain to me as a child. Now I'm doubtful. To paraphrase Greta, "the world has stolen my dreams."

We are now more likely to dissappear up our own brainstem into virtual reality than conquer the Galaxy.

A very thoughtful piece Morgoth.